Content from What is Web Scraping?

Last updated on 2026-01-22 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 20 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is web scraping and why is it useful?

- What are typical use cases for web scraping?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Be able to navigate around a website, understanding the concept of structured data

- Discuss how data can be extracted from web pages

- Sign in

- Setup

- Introduce self

- Code of conduct

- Intro questions

- Do you have a specific web scraping application in mind?

- Is there anything in particular which you would like to learn in this session?

- What is web scraping?

- Extracting information from websites

- Manual - faster to automate

- Collect data in usable format, e.g. .cvsv

- Similar to web indexing - more targeted

Example - Need to understand structure of a webpage

What is web scraping?

Web scraping is a technique for extracting information from websites. This can be done manually but it is usually faster, more efficient and less error-prone to automate the task.

Web scraping allows you to acquire non-tabular or poorly structured data from websites and convert it into a usable, structured format, such as a .csv file or spreadsheet.

Scraping is about more than just acquiring data: it can also help you archive data and track changes to data online.

It is closely related to the practice of web indexing, which is what search engines like Google do when mass-analysing the Web to build their indices. But contrary to web indexing, which typically parses the entire content of a web page to make it searchable, web scraping targets specific information on the pages visited.

For example, online stores will often scour the publicly available pages of their competitors, scrape item prices, and then use this information to adjust their own prices. Another common practice is “contact scraping” in which personal information like email addresses or phone numbers is collected for marketing purposes.

Web scraping is also increasingly being used by scholars to create data sets for text mining projects; these might be collections of journal articles or digitised texts. The practice of data journalism, in particular, relies on the ability of investigative journalists to harvest data that is not always presented or published in a form that allows analysis.

Example: Scraping parliamentary websites for contact information

- Point out:

- Looks quite well ordered

- Refine search

- Export options

- Human can easily work out what data represents

- Computer needs more information

- Slide - html

- Can see reasonably well structured

- Looks like table of data on webpage - quite different in the code

- Could get computer to pick out specific information

In this workshop, we will learn how to extract information from various web pages. Different webpages can have widely differing formats which will affect our decisions as to which method of scraping data might be appropriate.

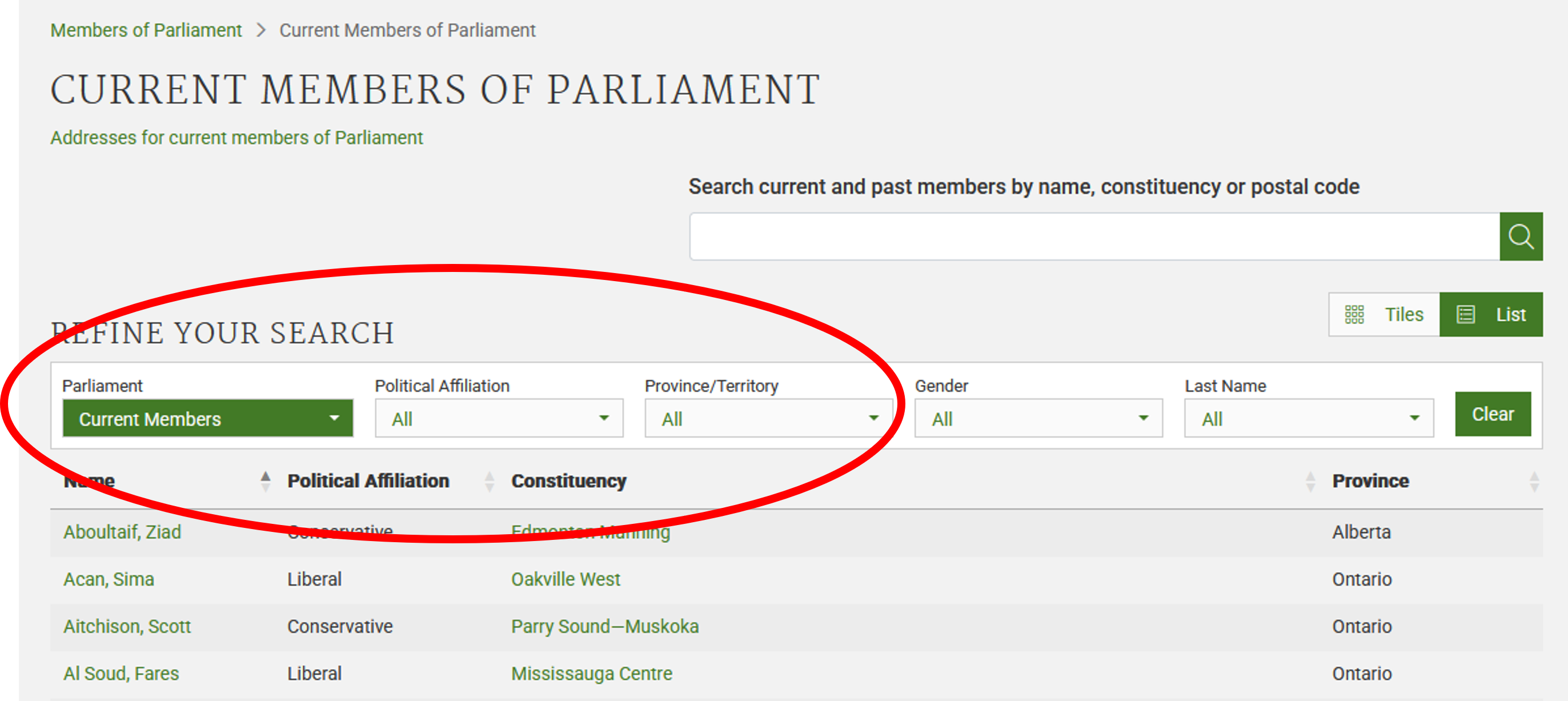

Before we can make such decisions we need to have some understanding of the makeup of a webpage. Let’s start by looking at the list of members of the Canadian parliament, which is available on the Parliament of Canada website

This is how this page appears in December 2025:

There are several features (circled in the image above) that make the data on this page easier to work with. The search, reorder, refine features and display modes hint that the data is actually stored in a (structured) database before being displayed on this page. The data can be readily downloaded either as a comma separated values (.csv) file or as XML for re-use in their own database, spreadsheet or computer program.

Even though the information displayed in the view above is not labelled, anyone visiting this site with some knowledge of Canadian geography and politics can see what information pertains to the politicians’ names, the geographical area they come from and the political party they represent. This is because human beings are good at using context and prior knowledge to quickly categorise information.

Computers, on the other hand, cannot do this unless we provide them with more information. If we examine the source HTML code of this page, we can see that the information displayed has a consistent structure:

HTML

(...)

<tr role="row" id="mp-list-id-25446">

<td data-sort="Allison Dean" class="sorting_1">

<a href="/members/en/dean-allison(25446)">

Allison, Dean

</a>

</td>

<td data-sort="Conservative">Conservative</td>

<td data-sort="Niagara West">

<a href="/members/en/constituencies/niagara-west(1124)">Niagara West</a>

</td>

<td data-sort="Ontario">Ontario</td>

</tr>

(...)Using this structure, we may be able to instruct a computer to look for all parliamentarians from Alberta and list their names and caucus information.

Structured vs unstructured data

When presented with information, human beings are good at quickly categorizing it and extracting the data that they are interested in. For example, when we look at a magazine rack, provided the titles are written in a script that we are able to read, we can rapidly figure out the titles of the magazines, the stories they contain, the language they are written in, etc. and we can probably also easily organize them by topic, recognize those that are aimed at children, or even whether they lean toward a particular end of the political spectrum. Computers have a much harder time making sense of such unstructured data unless we specifically tell them what elements data is made of, for example by adding labels such as this is the title of this magazine or this is a magazine about food. Data in which individual elements are separated and labelled is said to be structured.

- Canadian MPs - well structured

- What if data isn’t organised in such an obvious way?

- Unstructured

- British MPs

- Similar data - no way to download

- Slide -> UK MPs html

- Data structured for viewing - table of cards

- Less easy to see how data would be gathered

- Process automated by web scraping

- Slide -> definition

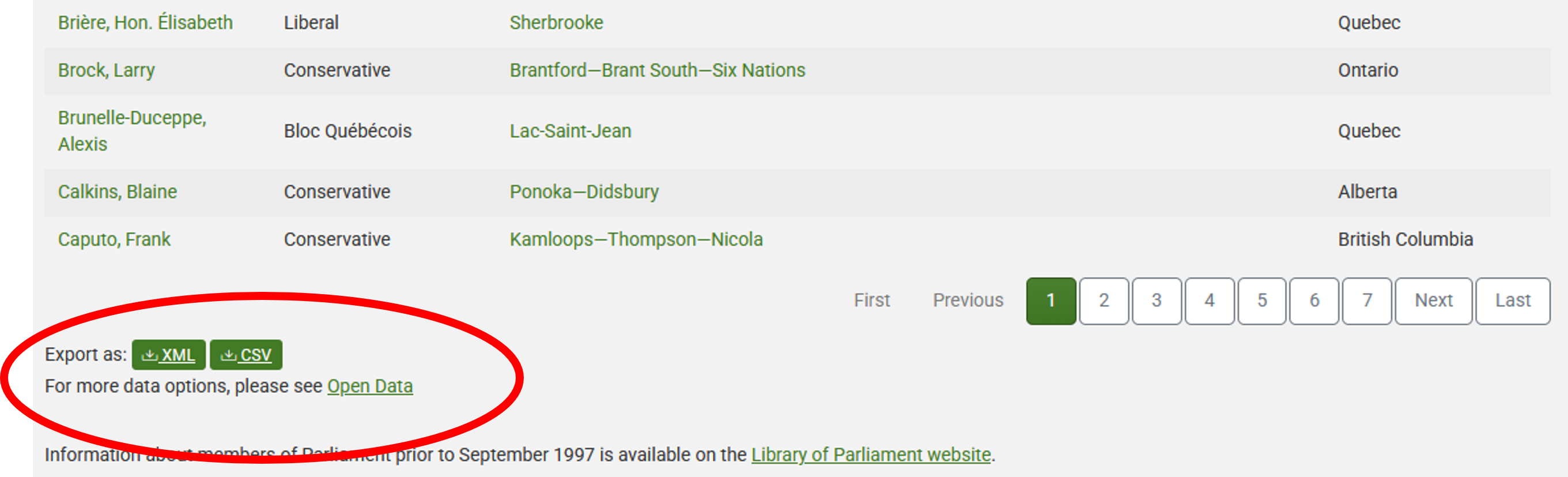

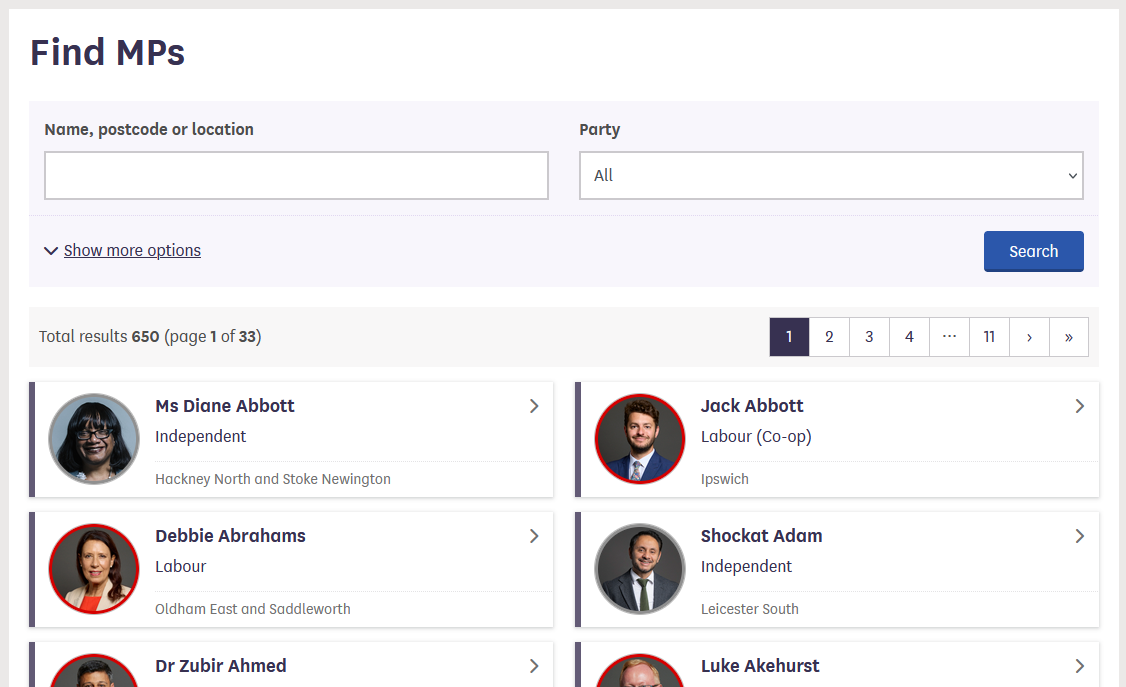

Let’s look now at the current list of members for the UK House of Commons.

This page also displays a list of names, political and geographical affiliation. There is a search box and a filter option, but no obvious way to download this information and reuse it.

Here is the code for this page:

HTML

(...)

<a class="card card-member" href="/member/172/contact">

<div class="card-inner">

<div class="content">

<div class="image-outer">

<div class="image"

aria-label="Image of Ms Diane Abbott"

style="background-image: url(https://members-api.parliament.uk/api/Members/172/Thumbnail); border-color: #909090;"></div>

</div>

<div class="primary-info">

Ms Diane Abbott

</div>

<div class="secondary-info">

Independent

</div>

</div>

<div class="info">

<div class="info-inner">

<div class="indicators-left">

<div class="indicator indicator-label">

Hackney North and Stoke Newington

</div>

</div>

<div class="clearfix"></div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</a>

(...)We see that this data has been structured for displaying purposes (it is arranged in rows inside a table) but the different elements of information are not clearly labelled.

What if we wanted to download this dataset and, for example, compare it with the Canadian list of MPs to analyze gender representation, or the representation of political forces in the two groups? We could try copy-pasting the entire table into a spreadsheet or even manually copy-pasting the names and parties in another document, but this can quickly become impractical when faced with a large set of data. What if we wanted to collect this information for every country that has a parliamentary system?

Fortunately, there are tools to automate at least part of the process. This technique is called web scraping.

“Web scraping (web harvesting or web data extraction) is a computer software technique of extracting information from websites.” (Source: Wikipedia)

Web scraping typically targets one web site at a time to extract unstructured information and put it in a structured form for reuse.

- Show UK MP tools

- Make sure really necessary to web scrape

Web scraping might not be necessary …

As useful as scraping is, there might be better options for the task. Choose the right (i.e. the easiest) tool for the job.

- Check whether or not you can easily copy and paste data from a site into Excel or Google Sheets. This might be quicker than scraping.

- Check whether there is data available on the website for download

(you may need to search around the website to find this but it may save

time overall).

- For example, the UK Parliament website has a large library of data published for re-use.

- Check if the site or service already provides an API to extract

structured data. If it does, that will be a much more efficient and

effective pathway.

- Good examples are the Facebook API, the X APIs or the YouTube comments API.

- The UK Parliament website that we have been looking at provides a set of APIs in its Developer Hub

- For much larger needs, Freedom of information Act (FOIA) requests can be useful. Be specific about the formats required for the data you want.

… but if it is

In the next episodes, we will continue exploring the examples above and try different techniques to extract the information they contain.

Before we launch into web scraping proper however, we need to look a bit more closely at how information is organized within an HTML document and how to build queries to access a specific subset of that information.

References

- Humans are good at categorizing information, computers not so much.

- Often, data on a web site is not properly structured, making its extraction difficult.

- Web scraping is the process of automating the extraction of data from web sites.

- Tools may be available on a web page which enable data to be downloaded directly.

Content from Anatomy of a web page

Last updated on 2026-01-28 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What’s behind a website, and how can I extract information from it?

- How can I find the code for a specific element on a web page?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Identify the structure and key components of an HTML document

- Explain how to use the browser developer tools to view the underlying html content of a web page

- Use the browser developer tool to find the html code for specific items on a web page

Introduction

Before we delve into web scraping properly, we will first spend some time introducing some of the techniques that are required to indicate exactly what should be extracted from the web pages we aim to scrape.

Here, we’ll develop an understanding of how content and data are structured on the web. We’ll start by exploring what HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) is and how it uses tags to organise and format content. Then, we’ll look at how to view the HTML source code for a web page and look at how browser developer tools can be used to search for specific elements on a webpage.

- html - uses tags to organise and format content.

- Slide - ask what people think it will do

- structured doc, elements marked by tags

- attributes - modify behaviour, appearance or functionality

- list of tags in notes

HTML quick overview

All websites have a Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) document behind them. Below is an example of HTML for a very simple webpage that contains just three sentences. As you look through it, try to imagine how the website would appear in a browser.

HTML

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Sample web page</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>h1 Header #1</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph tag</p>

<h2>h2 Sub-header</h2>

<p>A new paragraph, now in the <b>sub-header</b></p>

<h1>h1 Header #2</h1>

<p>

This other paragraph has two hyperlinks,

one to <a href="https://carpentries.org/">The Carpentries homepage</a>,

and another to the

<a href="https://carpentries.org/workshops/past-workshops/">past workshops</a> page.

</p>

</body>

</html>This text has been saved with a .html extension, SampleWebpageCode.html. If you open it in your web browser, the browser will interpret the markup language and display a nicely formatted web page as below.

When you open an HTML file in your browser, what it’s really doing is

reading a structured document made up of elements, each

marked by tags inside angle brackets (< and >).

For instance, the HTML root element, which delimits the beginning and

end of an HTML document, is identified by the <html>

tag.

Most elements have both an opening tag and a closing tag, which

define the start and end of that element. For example, in the simple

website we looked at earlier, the head element begins with

<head> and ends with </head>.

Because elements can be nested inside one another, an HTML document forms a tree structure, where each element is a node that can contain child nodes, as illustrated in the image below.

Finally, we can define or modify the behaviour, appearance, or

functionality of an element using attributes.

Attributes appear inside the opening tag and consist of a name and a

value, formatted like name="value".

For example, in the simple website, we added a hyperlink using the

<a>...</a> tags. To specify the destination

URL, we used the href attribute inside the opening

<a> tag like this:

<a href="https://carpentries.org/workshops/past-workshops/">past workshops</a>.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of common HTML elements and their purposes:

-

<hmtl>...</html>: The root element that contains the entire document. -

<head>...</head>: Contains metadata such as the page title that the browser displays. -

<body>...</body>: Contains the content that will be shown on the webpage. -

<h1>...</h1>, <h2>...</h2>, <h3>...</h3>: Define headers of levels 1, 2, 3, and so on. -

<p>...</p>: Represents a paragraph. -

<a href="">...</a>: Creates a hyperlink; the destination URL is set with the href attribute. -

<img src="" alt="">: Embeds an image, with the image source specified bysrcand alternative text provided byalt. It doesn’t have an opening tag. -

<table>...</table>, <th>...</th>, <tr>...</tr>, <td>...</td>: Define a table structure, with headers (<th>), rows (<tr>), and cells (<td>). -

<div>...</div>: Groups sections of HTML content together. -

<script>...</script>: Embeds or links to JavaScript code.

In the list above, we mentioned some attributes specific to hyperlink

(<a>) and image (<img>) elements,

but there are also several global attributes that most HTML elements can

have. These are especially useful for identifying elements when web

scraping:

-

id="": Assigns a unique identifier to an element; this ID must be unique within the entire HTML document. -

title="": Provides extra information about the element, shown as a tooltip when the user hovers over it. -

class="": Applies a common styling or grouping to multiple elements at once.

This A to Z List gives a comprehensive list of html tags.

- CSS gives separation between display format and content

- uses rules applied to html elements by selectors

- can be useful for targeting elements when scraping

Slide - CSS added to head tag

CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) is code which allows the way that a web page is displayed (colours, fonts etc) to be separated from the content. It allows the same styles to be applied to a set of HTML documents without the need to specify them in each document.

CSS uses rule sets which are applied to the HTML elements using selectors.

You may see selectors applied to HTML elements by tag, class or ID. These may be useful for targeting elements when web scraping. The CSS rules may be applied using atag in the HTML file or may be in a separate .css file linked from the HTML file.

An example of two style rules applied to our HTML example are shown below. They can be viewed by opening the WebpageCSS.html file.

HTML

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Sample web page</title>

<style>

/* CSS Rule */

h1 {

color: blue;

/* Property: value */

font-size: 24px;

}

p {

color: green;

font-size: 16px;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>h1 Header #1</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph tag</p>

<h2>h2 Sub-header</h2>

<p>A new paragraph, now in the <b>sub-header</b></p>

<h1>h1 Header #2</h1>

<p>

This other paragraph has two hyperlinks,

one to <a href="https://carpentries.org/">The Carpentries homepage</a>,

and another to the

<a href="https://carpentries.org/workshops/past-workshops/">past workshops</a> page.

</p>

</body>

</html>For more information this CSS Introduction and CSS Cheat Sheet provide a good starting point.

To summarize: elements are identified by tags, and attributes let us assign properties or identifiers to those elements. Understanding this structure will make it much easier to extract specific data from a website.

Inspecting the web page source code

We will use the HTML code that describes this very page you are reading as an example. By default, a web browser interprets the HTML code to determine what markup to apply to the various elements of a document, and the code is invisible. To make the underlying code visible, all browsers have a function to display the raw HTML content of a web page.

- Web pages tend to be generated by other programs

- Adds to the complexity

- Source of this page initially seems complex

- hunt for the tags

- Ctrl+f to search

Exercise: Display the source of this page

Using your favourite browser, display the HTML source code of this page.

Tip: in most browsers, all you have to do is do a right-click anywhere on the page and select the “View Page Source” option (“Show Page Source” in Safari).

Another tab should open with the raw HTML that makes this page. See if you can locate its various elements, where the head and body elements start and end. See if you can pickout this challenge box in particular.

You will see that this webpage is quite complex and it may not be easy to pick out the elements that you are looking for. Many webpages are automatically generated and may not be laid out in the straightforward manner of our initial, very simple, example.

Try searching for head> or body> to locate both the start and end of these sections.

Even though these may be difficult to locate, you will see that the same overall structure is still used for the webpage.

The HTML structure of the page you are currently reading looks something like this (most text and elements have been removed for clarity):

HTML

<!doctype html>

<html lang="en" data-bs-theme="auto">

<head>

(...)

<title>Introduction to Web Scraping: Anatomy of a web page</title>

(...)

</head>

<body>

(...)

</body>

</html>We can see from the source code that the title of this page is in a

title element that is itself inside the head

element, which is itself inside an html element that

contains the entire content of the page.

Say we wanted to tell a web scraper to look for the title of this

page, we would use this information to indicate the path the

scraper would need to follow as it navigates through the HTML content of

the page to reach the title element. We can search for

specific items in the source page code using the built in developer

console.

Display the console in your browser

- In Firefox, use the More Tools > Web Developer Tools menu item.

- In Chrome, use the More tools > Developer tools menu item.

- In Safari, use the Develop > Show Error Console menu item. If your Safari browser doesn’t have a Develop menu, you must first enable this option in the Preferences, see above.

Here is how the console looks like in the Chrome browser:

By default the console will probably open in the Console tab. For now, don’t worry too much about error messages if you see any in the console when you open it. We will be using the Elements tab to locate specific items in the web page.

- Back to Canadian MPs page

- May need to expand elements

- Member data stored in table table, td and tr tags

- Hover over element in console to highlight on page

Locate code for specific elements

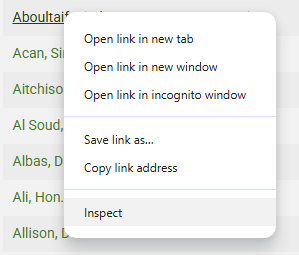

To find the code for a specific item on a web page, hover over it and right click, selecting Inspect from the dialog displayed (shown below).

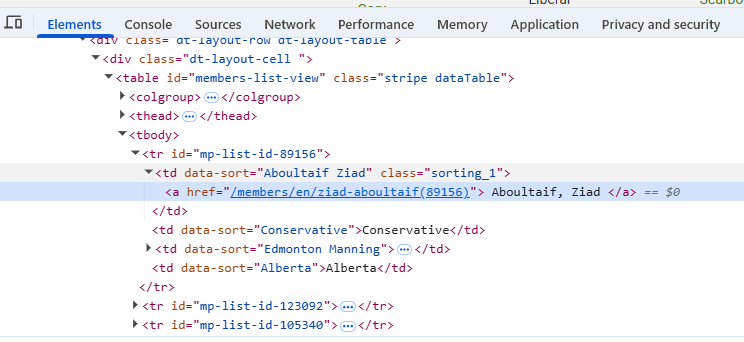

This will automatically move to the Elements tab in the developer console (opening the developer console if not already open) and display the section of code for the selected element. The specific line of code for the element will be highlighted. In the example below a name was selected on the Canadian MPs webpage resulting in the code below:

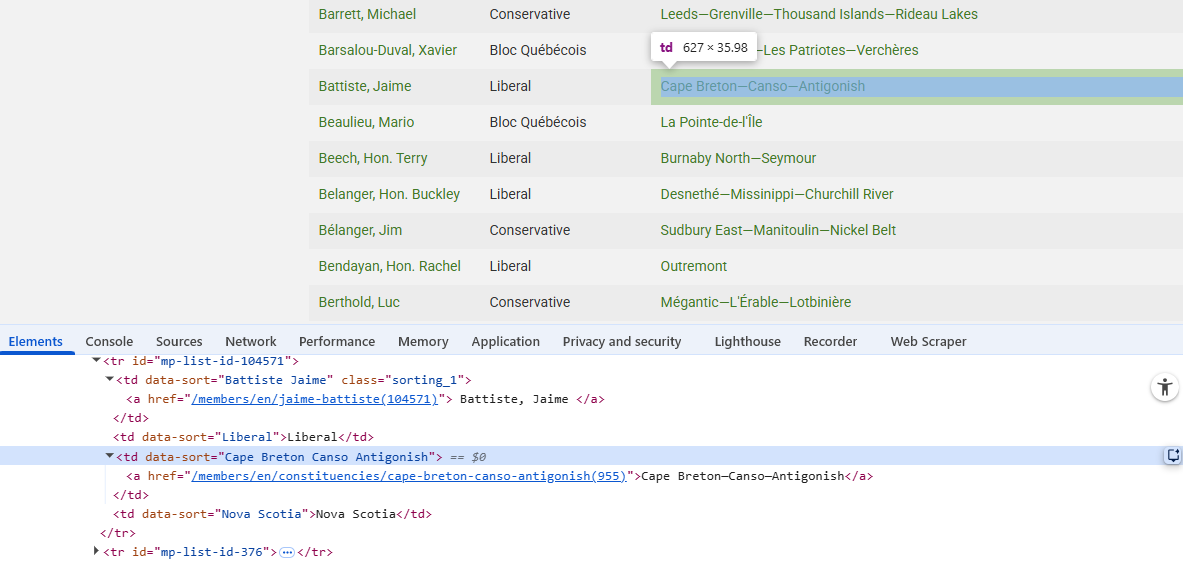

Conversly, by hovering over a line of code in the Elements tab, the corresponding element will be highlighted on the web page, showing the tag and size of the element. This is shown below:

Identify element tag for extracting MP names

Go back to the UK House of Commons webpage. Use the developer console to identify what you might need to search for in order to extract a list of MPs names.

Can you see an issue with the data collected if you just searched on this particular page?

The class “primary-info” contains the text for the names.

Note that this information is spread over several pages. It may be necessary to make use of the links for further pages in order to extract all of the required information.

Dynamic websites

We are not going to cover these in detail in this lesson but you should be aware of dynamic websites and how the HTML code observed might differ between these and a static website with no interactive elements.

Visit this practice webpage created by Hartley Brody for learning and practicing web scraping: Oscar Winning Films (but first, read the terms of use). Select “2015” to display that year’s Oscar-winning films.

Now try viewing the HTML behind the page using the View Page Source tool in your browser.

Challenge

Can you find the Best Picture winner Spotlight anywhere in the HTML?

Can you find any of the other movies or the data from the table?

If not, how could you scrape this page?

- View Page Source shows html from when the page is loaded

- Selecting 2015 triggers the script

- Inspect then displays the rendered html

When you explore a page like this, you’ll notice that the movie data (including the title Spotlight) isn’t present in the initial HTML source. That’s because the website uses JavaScript to load the information dynamically. JavaScript is a programming language that runs in your browser and allows websites to fetch, process, and display content on the fly — often in response to user actions, like clicking a button.

When you select “2015”, your browser runs JavaScript (triggered by

one of the <script> elements in the HTML) to retrieve

the relevant movie information from the web server and dynamically

update the table. This makes the page feel more interactive, but it also

means that the initial HTML you see doesn’t contain the movie data

itself.

You can observe this difference when using the “View page source” and “Inspect” tools in your browser: “View page source” shows the original HTML sent by the server, before any JavaScript runs. “Inspect” shows the rendered HTML, after JavaScript has executed and updated the page content.

- Every website is built on an HTML document that structures its content.

- An HTML document is composed of elements, usually defined by an

opening

and a closing . - Elements can have attributes that define their properties, written

as

. - CSS may be used to control the appearance of the rendered webpage.

- Dynamic webpages may have content which isn’t loaded until the item is selected.

Content from Manually scrape data using browser extensions

Last updated on 2026-01-22 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I get started scraping data off the web?

- How do I assess the most appropriate method to scrape data?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Understand the different tools for accessing web page data

- Use the WebScraper tool to extract data from a web page

- Assess the appropriate method for gathering the required data

Using the Web Scraper Chrome extension

Now we are finally ready to do some web scraping using Web Scraper Chrome extension. If you haven’t it installed on your machine, please refer to the Setup instructions.

For this lesson, we will again be using the UK Members of Parliament webpages. We are interested in scraping a list of MPs and their constituencies with the help of Web Scraper.

First, let’s focus our attention on the first webpage with the list of

MPs.

We are interested in downloading the list of MP’s names and their

constituency.

There are two ways of using Web Scraper, either using the Wizard GUI or using selectors in the developer tools. The wizard gives an easy to use interface but may be less flexible and doesn’t provide the ability to customise that is possible using the developer tools.

Using the Web Scraper wizard

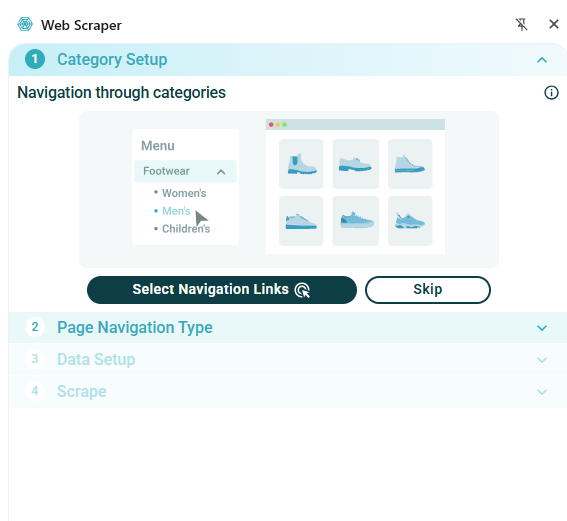

With the extension installed the Wizard window can be opened by selecting the Web Scraper icon on the browser toolbar:

The wizard allows you to select any links to navigate to other pages. In our example we don’t need to do this so we will select Skip In the Page Navigation Type tab, select whether to make selections from the listing page or whether to open links

- We will use the Listing page option

- Select Continue - this will auto-generate selectors and give a preview of the data

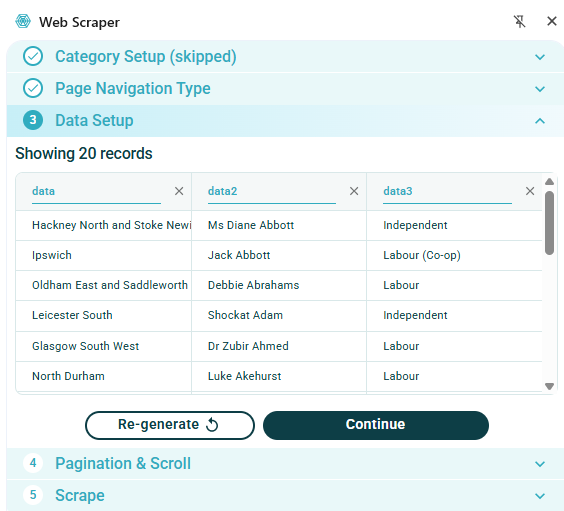

The image below shows an example of the data which is automatically extracted from this web page without any selection:

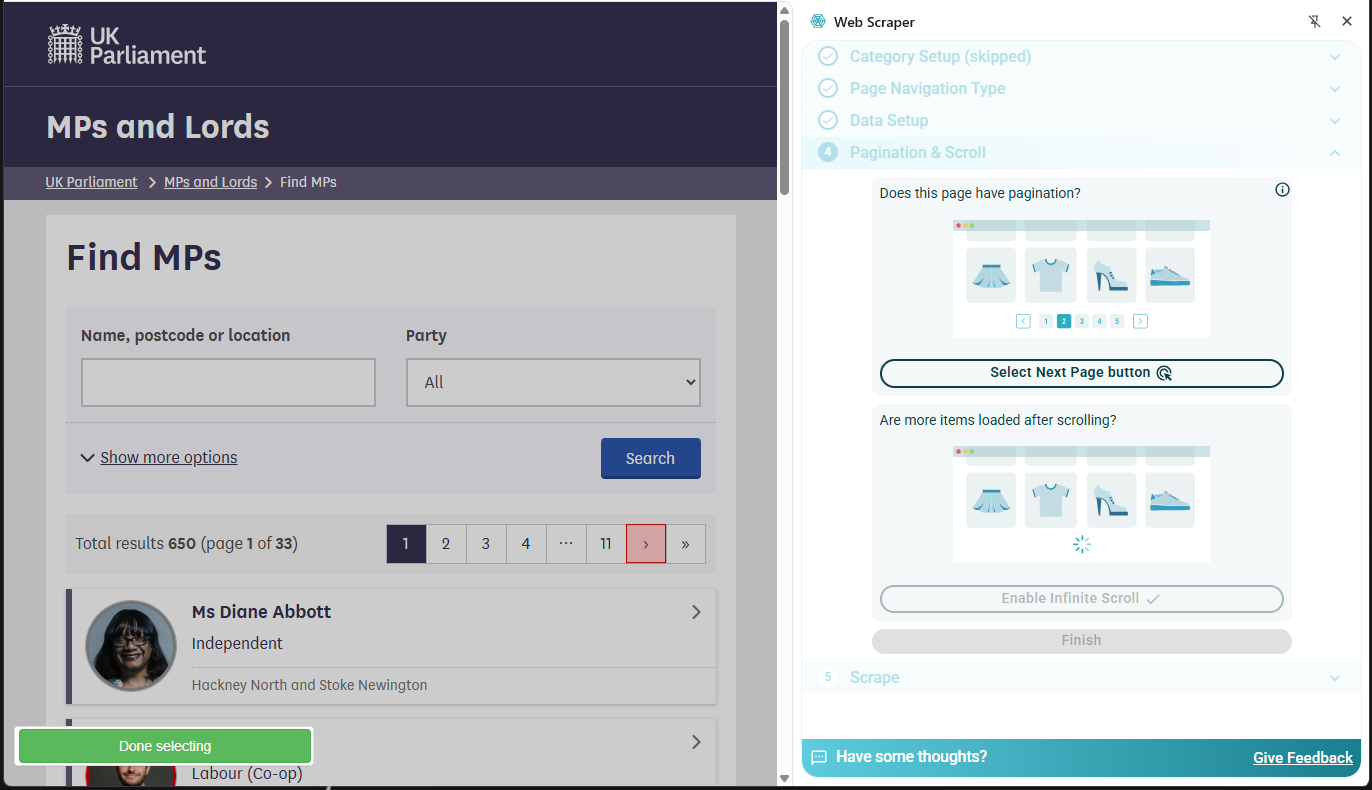

Note that this has only gathered the names of MPs for one page, collecting about 20 entries out of a total of 650. The next section Pagination & Scroll allows multiple pages to be selected for scraping:

- Choose Select Next Page button

- Select the appropriate means of selecting more pages. This could be either a set of numbered pages or a ‘next page’ button. Several buttons can be selected if needed.

- On completion click the green Done selecting button.

On selection of the Finish button the dialog will show that scraper configuration is ready and the Scrape the page button can be selected.

Now data has been scraped for all 650 MPs from all pages:

The data scraped can now be downloaded as either a .xlsx or .csv file.

Using Web Scraper with the browser developer console

- Open the Developer Tools and open the Web Scraper

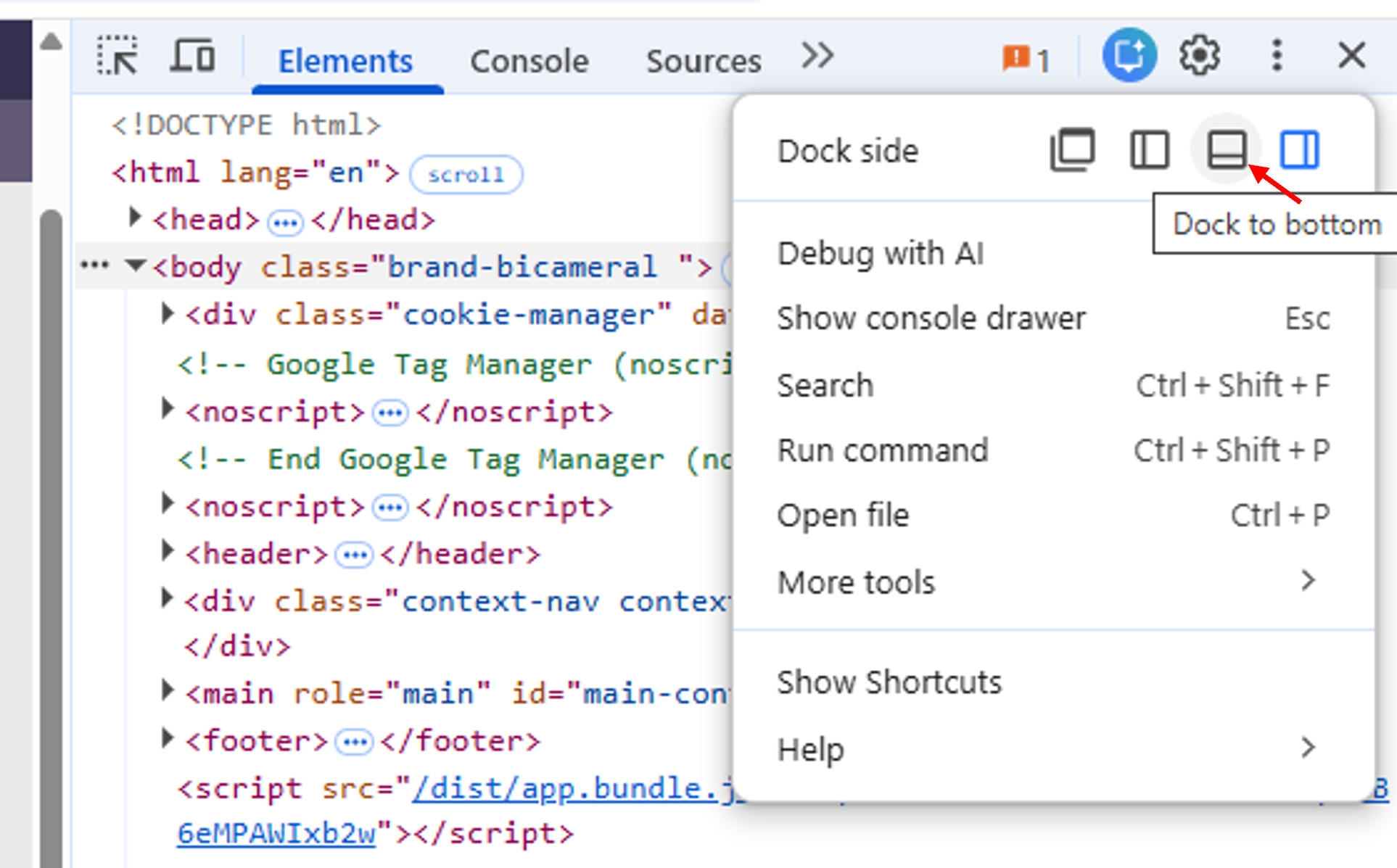

tab

- If the developer tools are docked at the side of the screen use the three dots a the top right of the dialog and select the option to dock at the bottom (see below)

Dialog to select Developer Tools docking position

Dialog to select Developer Tools docking position

Web Scraper works with a Sitemap

Should see sitemap generated by previous exercise

May need to spend time inspecting code to decide on best selectors to use

-

Create new sitemap

- Can just select pages 1 and 2 OR

- Use search to select Lib Dem so that only 4 pages

-

Add new selector

- Show different selectors available

The Web Scraper extension works on a “Sitemap”. The previous exercise will already have created a sitemap and this will be listed in the opening window on the tab. Alternatively, a new sitemap can be created: - Select Create new sitemap-> Create Sitemap - Add a Sitemap name and Start URL for the webpage you wish to scrape - Click Create Sitemap

When a sitemap has been created then selectors can be created to govern how the webpage will be scraped. For a webpage created by the Wizard, the selectors generated automatically can be inspected, edited and new selectors created as required.

It is a good idea to spend some time navigating the website and taking a look at the underlying code, using the Inspect facility, to decide on the best way to set up the selectors. The code will show the type of elements underlying the items on the webpage and may help with deciding how to scrape the page.

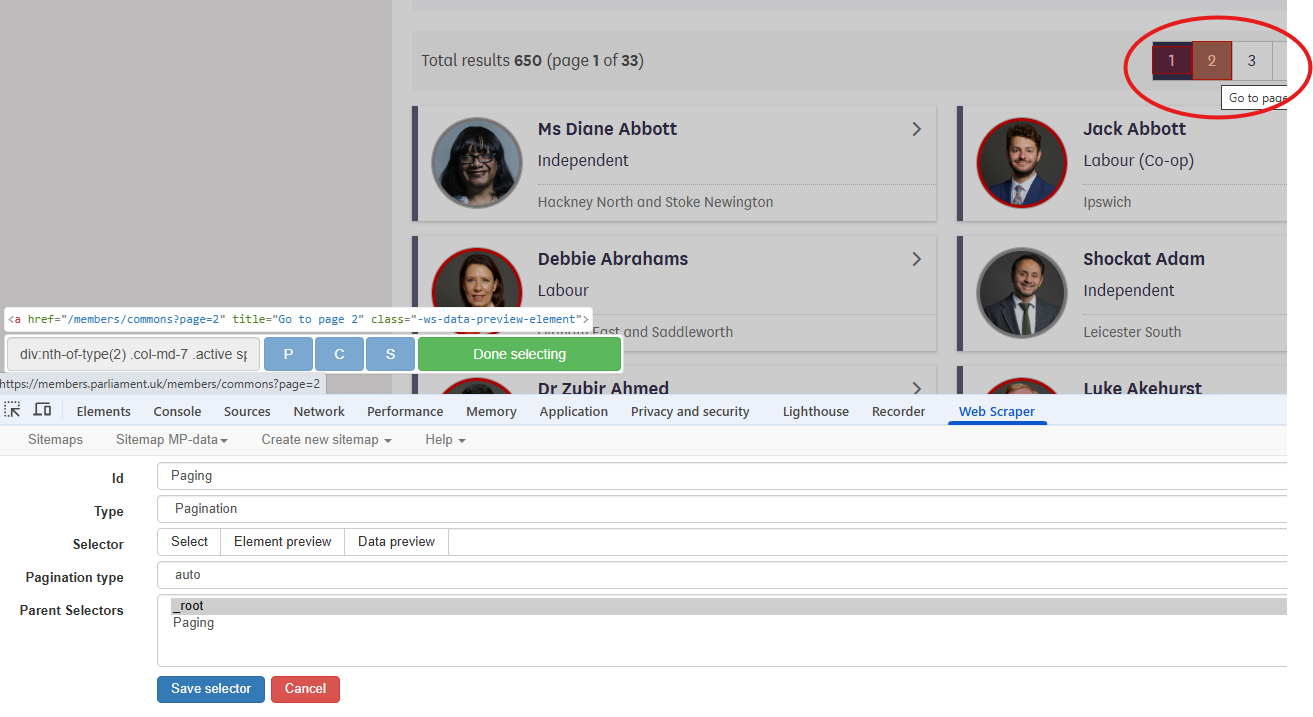

The MP information data is spread across several pages. The first selector that we will create will enable the scraper to automatically scrape multiple pages.

- Select the Add new selector button. In the resulting

dialog:

- Choose an Id for the selector, e.g. Paging

- The type menu offers a drop down menu of available selectors. In this case, we will choose the Pagination selector

- Use the Select button to select the relevant elements on the webpage. In this case the pagination uses the numbered boxes at the top or bottom of the page. More than one selection can be made by using Shift+Enter. In the example shown below, just two pages have been selected.

- The Element Preview button can be used to check that the correct items have been selected.

- The Data Preview button will show the data that will result from this scraping operation.

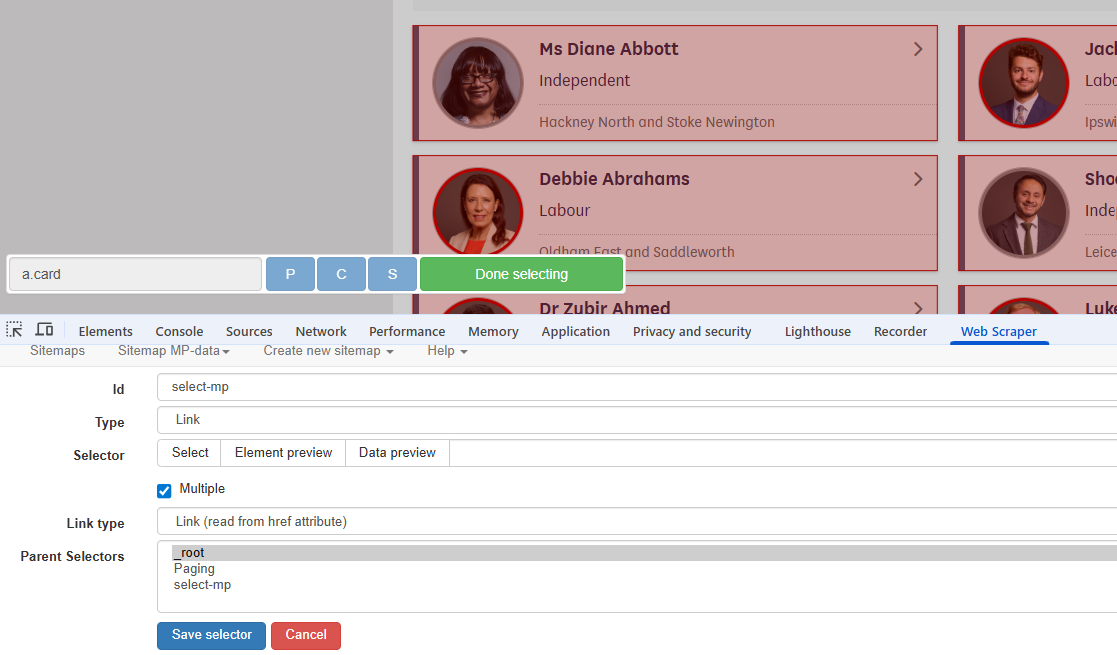

The information to be scraped is on the page navigated to by selecting one of the MP list boxes. We will set up a selector to select each box on the page. Note that, because the pagination selector has already been set up, it is only necessary to do this for one page.

- Information is on selected page

- Click on selector - breadcrumb changes

The next information to be selected is on the page arrived at by the links selected in the previous step. By clicking on the selector just created in the list it can be seen that the link breadcrumbs update:

- Select the Paging row in the dialog

- Create a new selector as before, this time choosing a Link selector

- When using the Select button all MP list boxes can be selected by clicking on a second box.

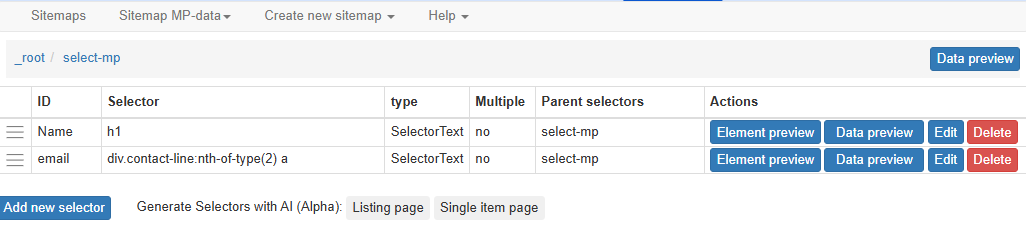

- Check the Multiple option

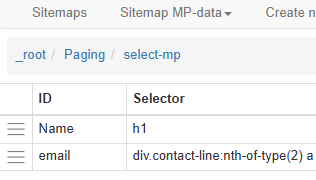

Again, the next information to be selected is on the page arrived at by the links selected in the previous step. By clicking on the select-mp selector in the list it can be seen that the link breadcrumbs have again been updated:

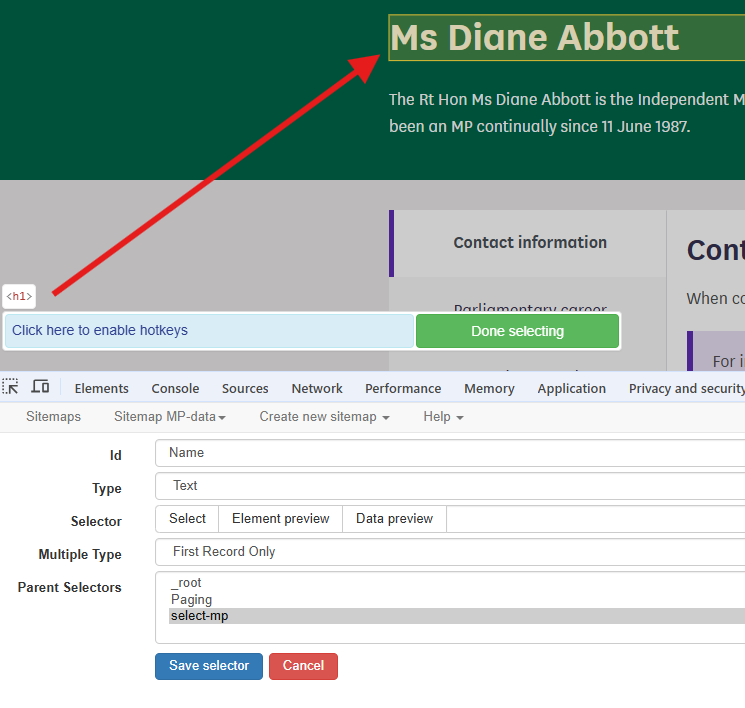

We now need to navigate to one of the MP pages by clicking on one of the list boxes. The required data can now be gathered by adding more selectors.

- Create a Text type selector

- Select the field containing the name

We can use the same method to create a selector for the email address. There should now be two selectors within the select-mp page.

The sitemap is now ready for scraping. Select Sitemap name -> Scrape. The Request interval and Page load delay options can be left at the default 2000ms. Clicking the Start scraping button will start the scraping process. A window will open, showing the pages being accessed in the scraping process.

On completion of scraping it may be necessary to click the Refresh button in order to view the data. A table will be displayed showing the data extracted. The Sitemap name -> Export Data option allows export in either .xlsx or .csv format.

MP-data.xlsx is the file downloaded after the scraping exercise described above. On examination of this file, it can be seen that all of the MP’s names have been extracted but the list of email addresses is incomplete.

Challenge

MP-data.xlsx is the file downloaded after the scraping exercise described above. On examination of this file, it can be seen that all of the MP’s names have been extracted but the list of email addresses is incomplete.

Why do you think that there are some email addresses missing? - Take a look at the code for the email address information. - Compare the information for MPs where the email address was found and where it was not

- Slide - code for Diane Abbott email address

- 2nd contact-line

- only one for Jack Abbott

- on inspection can search for ‘Email Address’

The code for the email address on the Ms Diane Abbott page is shown below:

HTML

(...)

<div class="col-md-7">

<div class="contact-line">

<span class="label">Phone Number:</span>

<a href="tel:020 7219 4426">020 7219 4426</a>

</div>

<div class="contact-line">

<span class="label">Email Address:</span>

<a href="mailto:diane.abbott.office@parliament.uk"> diane.abbott.office@parliament.uk</a>

</div>

</div>

(...)If we look at the selector code: “div.contact-line:nth-of-type(2) a” we can see that looks like it has picked out the second “contact-line” class and then used the text from the “a” tag. If we look at the similar section of code for an MP with just an email address in the contacts (no phone number) then we can see that a selector which searches for the second element will not yield a result.

Web Scraper includes some extra functionality which allows a more explicit search to be carried out using JQuery selectors. It is beyond the scope of this lesson to cover this in detail. There is information in the Web Scraper JQuery Selectors documentation.

We will look at how to use the contains option to extract the complete list of email addresses.

Using JQuery to refine selector options

The JQuery contains value can be used to target elements which contain a particular string. Inspection of the “contact-line” class shows that the email address item contains the string “Email Address”. The selector can be edited manually to

div.contact-line:contains(‘Email Address’) a

This will now only target the contact-line elements which contain the “Email Address” text.

Inspection of the new downloaded spreadsheet shows that all of the emails have now been extracted.

Challenge

Modify your sitemap to also gather the phone number information for each MP

- Data that is relatively well structured (in a table) is relatively easily to scrape.

- More often than not, web scraping tools need to be told what to scrape.

- JQuery can be used to define more precisely what information is to be scraped.

Content from Ethics and Legality of Web Scraping

Last updated on 2026-01-14 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- When is web scraping OK and when is it not?

- Is web scraping legal? Can I get into trouble?

- What are some ethical considerations to make?

- What can I do with the data that I’ve scraped?

Objectives

After completing this episode, participants should be able to…

- Discuss the legal and ethical implications of web scraping

- Establish a code of conduct

The rights, wrongs, and legal barriers to scraping

Now that we have seen several different ways to scrape data from websites and are ready to start working on potentially larger projects, we may ask ourselves whether there are any legal implications of writing a piece of computer code that downloads information from the Internet.

In this section, we will be discussing some of the issues to be aware of when scraping websites, and we will establish a code of conduct (below) to guide our web scraping projects.

This section does not constitute legal advice

Please note that the information provided on this page is for information purposes only and does not constitute professional legal advice on the practice of web scraping.

If you are concerned about the legal implications of using web scraping on a project you are working on, it is probably a good idea to seek advice from a professional, preferably someone who has knowledge of the intellectual property (copyright) legislation in effect in your country.

The internet isn’t as open as it once was. What used to be a vast, freely accessible source of information has become a valuable reservoir of data —especially for training machine learning and generative AI models. In response, many social media platforms and website owners have either started monetizing access to their data or taken steps to protect their resources from being overwhelmed by automated bots.

As a result, it’s increasingly common for websites to include

explicit prohibitions against web scraping in their Terms of Service

(TOS). To avoid legal or ethical issues, it’s essential to check both

the TOS and the site’s robots.txt file before scraping.

You can usually find a site’s robots.txt file by

appending /robots.txt to the root of the domain—for

example: https://facebook.com/robots.txt (not

https://facebook.com/user/robots.txt). Both the TOS and

robots.txt will help you understand what is allowed and

what isn’t, so it’s important to review them carefully before

proceeding.

Challenge

Visit Facebook’s Terms of Service and its robots.txt file. What do they say about web scraping or collecting data using automated means? Compare it to Reddit’s TOS and Reddit’s robots.txt.

Don’t break the web: Denial of Service attacks

The first and most important thing to be careful about when writing a web scraper is that it typically involves querying a website repeatedly and accessing a potentially large number of pages. For each of these pages, a request will be sent to the web server that is hosting the site, and the server will have to process the request and send a response back to the computer that is running our code. Each of these requests will consume resources on the server, during which it will not be doing something else, like for example responding to someone else trying to access the same site.

If we send too many such requests over a short span of time, we can prevent other “normal” users from accessing the site during that time, or even cause the server to run out of resources and crash.

In fact, this is such an efficient way to disrupt a web site that hackers are often doing it on purpose. This is called a Denial of Service (DoS) attack.

Since DoS attacks are unfortunately a common occurence on the Internet, modern web servers include measures to ward off such illegitimate use of their resources. They are watchful for large amounts of requests appearing to come from a single computer or IP address, and their first line of defense often involves refusing any further requests coming from this IP address.

A web scraper, even one with legitimate purposes and no intent to bring a website down, can exhibit similar behaviour and, if we are not careful, result in our computer being banned from accessing a website.

The good news is that a good web scraper, such as the WebScraper extension used in this lesson, recognizes that this is a risk and includes measures to prevent our code from appearing to launch a DoS attack on a website. This is mostly done by inserting a random delay between individual requests, which gives the target server enough time to handle requests from other users between ours.

Don’t steal: Copyright and fair use

It is important to recognize that in certain circumstances web scraping can be illegal. If the terms and conditions of the web site we are scraping specifically prohibit downloading and copying its content, then we could be in trouble for scraping it.

In practice, however, web scraping is a tolerated practice, provided reasonable care is taken not to disrupt the “regular” use of a web site, as we have seen above.

In a sense, web scraping is no different than using a web browser to visit a web page, in that it amounts to using computer software (a browser vs a scraper) to acccess data that is publicly available on the web.

In general, if data is publicly available (the content that is being scraped is not behind a password-protected authentication system), then it is OK to scrape it, provided we don’t break the web site doing so. What is potentially problematic is if the scraped data will be shared further. For example, downloading content off one website and posting it on another website (as our own), unless explicitely permitted, would constitute copyright violation and be illegal.

However, most copyright legislations recognize cases in which reusing some, possibly copyrighted, information in an aggregate or derivative format is considered “fair use”. In general, unless the intent is to pass off data as our own, copy it word for word or trying to make money out of it, reusing publicly available content scraped off the internet is OK.

Better be safe than sorry

Be aware that copyright and data privacy legislation typically differs from country to country. Be sure to check the laws that apply in your context. For example, in Australia, it can be illegal to scrape and store personal information such as names, phone numbers and email addresses, even if they are publicly available.

If you are looking to scrape data for your own personal use, then the above guidelines should probably be all that you need to worry about. However, if you plan to start harvesting a large amount of data for research or commercial purposes, you should probably seek legal advice first.

If you work in a university, chances are it has a copyright office that will help you sort out the legal aspects of your project. The university library is often the best place to start looking for help on copyright.

Be nice: ask and share

Depending on the scope of your project, it might be worthwhile to consider asking the owners or curators of the data you are planning to scrape if they have it already available in a structured format that could suit your project. If your aim is do use their data for research, or to use it in a way that could potentially interest them, not only it could save you the trouble of writing a web scraper, but it could also help clarify straight away what you can and cannot do with the data.

On the other hand, when you are publishing your own data, as part of a research project, documentation or a public website, you might want to think about whether someone might be interested in getting your data for their own project. If you can, try to provide others with a way to download your raw data in a structured format, and thus save them the trouble to try and scrape your own pages!

Web scraping Code of Conduct

To conclude, here is a brief code of conduct you should keep in mind when doing web scraping:

Ask nicely whether you can access the data in another way. If your project relies on data from a particular organization, consider reaching out to them directly or checking whether they provide an API. With a bit of luck they might offer the data you need in a structured format, saving you time and effort.

-

Don’t download content that’s clearly not public. For example, academic journal publishers often impose strict usage restrictions on their databases. Mass-downloading PDFs can violate these rules and may get you —or your university librarian— into trouble.

If you need local copies for a legitimate reason (e.g., text mining), special agreements may be possible. Your university library is a good place to start exploring those options.

Check your local legislation. Many countries have laws protecting personal information, such as email addresses or phone numbers. Even if this data is visible on a website, scraping it could be illegal depending on your jurisdiction (e.g., in Australia).

Don’t share scraped content illegally. Scraping for personal use is often considered fair use, even when it involves copyrighted material. But sharing that data, especially if you don’t have the rights to distribute it, can be illegal.

Share what you can. If the scraped data is public domain or you’ve been granted permission to share it, consider publishing it for others to reuse (e.g., on datahub.io). Also, if you wrote a scraper to access it, sharing your code (e.g., on GitHub) can help others learn from and build on your work.

Publish your own data in a reusable way. Make it easier for others by offering your data in open, software-agnostic formats like CSV, JSON, or XML. Include metadata that describes the content, origin, and intended use of the data. Ensure it’s accessible and searchable by search engines.

-

Don’t break the Internet. Some websites can’t handle high volumes of requests. If your scraper is recursive (i.e., it follows links), test it first on a small subset.

Be respectful by setting delays between requests and limiting the rate of access. You’ll learn more about how to do this in the next episode.

Following these guidelines helps ensure that your scraping is ethical, legal, and considerate of the broader web ecosystem.

Other notes

- Boundaries for using/modifying user-agents

- Obey robots.txt

- Respect rate limits

- If unsure contact site administrator to seek permission to scrape

- Copyright laws - can legally scrape publically available data but republishing or reusing data may require permission

- Web scraping is, in general, legal and won’t get you into trouble.

- Always review and respect a website’s Terms of Service (TOS) before scraping its content.

- There are a few things to be careful about, notably don’t overwhelm a web server and don’t steal content.

- Be nice. In doubt, ask.