Working With Files and Directories

Overview

Teaching: 25 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How can I create, copy, and delete files and directories?

How can I edit files?

Objectives

Create a directory hierarchy that matches a given diagram.

Create files in that hierarchy using an editor or by copying and renaming existing files.

Delete specified files and/or directories.

We now know how to explore files and directories,

but how do we create them in the first place?

Let’s go back to our data-shell directory on the Desktop

and use ls -F to see what it contains:

$ pwd

/Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell

$ ls -F

creatures/ data/ molecules/ north-pacific-gyre/ notes.txt pizza.cfg solar.pdf writing/

Let’s create a new directory called thesis using the command mkdir thesis

(which has no output):

$ mkdir thesis

As you might guess from its name,

mkdir means “make directory”.

Since thesis is a relative path

(i.e., doesn’t have a leading slash),

the new directory is created in the current working directory:

$ ls -F

creatures/ data/ molecules/ north-pacific-gyre/ notes.txt pizza.cfg solar.pdf thesis/ writing/

Two ways of doing the same thing

Using the shell to create a directory is no different than using a file explorer. If you open the current directory using your operating system’s graphical file explorer, the

thesisdirectory will appear there too. While they are two different ways of interacting with the files, the files and directories themselves are the same.

Good names for files and directories

Complicated names of files and directories can make your life painful when working on the command line. Here we provide a few useful tips for the names of your files.

Don’t use whitespaces.

Whitespaces can make a name more meaningful but since whitespace is used to break arguments on the command line it is better to avoid them in names of files and directories. You can use

-or_instead of whitespace.Don’t begin the name with

-(dash).Commands treat names starting with

-as options.Stick with letters, numbers,

.(period or ‘full stop’),-(dash) and_(underscore).Many other characters have special meanings on the command line. We will learn about some of these during this lesson. There are special characters that can cause your command to not work as expected and can even result in data loss.

If you need to refer to names of files or directories that have whitespace or another non-alphanumeric character, you should surround the name in quotes (

"").

Since we’ve just created the thesis directory, there’s nothing in it yet:

$ ls -F thesis

Let’s change our working directory to thesis using cd,

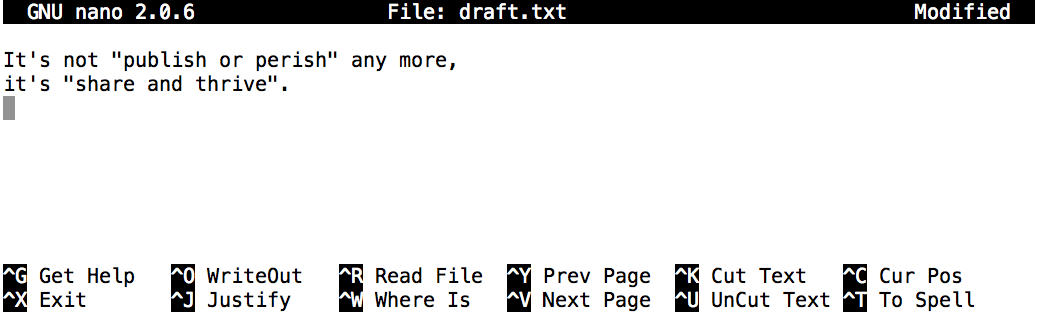

then run a text editor called Nano to create a file called draft.txt:

$ cd thesis

$ nano draft.txt

Which Editor?

When we say, “

nanois a text editor,” we really do mean “text”: it can only work with plain character data, not tables, images, or any other human-friendly media. We use it in examples because it is one of the least complex text editors. However, because of this trait, it may not be powerful enough or flexible enough for the work you need to do after this workshop. On Unix systems (such as Linux and Mac OS X), many programmers use Emacs or Vim (both of which require more time to learn), or a graphical editor such as Gedit. On Windows, you may wish to use Notepad++. Windows also has a built-in editor callednotepadthat can be run from the command line in the same way asnanofor the purposes of this lesson.No matter what editor you use, you will need to know where it searches for and saves files. If you start it from the shell, it will (probably) use your current working directory as its default location. If you use your computer’s start menu, it may want to save files in your desktop or documents directory instead. You can change this by navigating to another directory the first time you “Save As…”

Text vs. Whatever

We usually call programs like Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer “text editors”, but we need to be a bit more careful when it comes to programming. By default, Microsoft Word uses

.docxfiles to store not only text, but also formatting information about fonts, headings, and so on. This extra information isn’t stored as characters, and doesn’t mean anything to tools likehead: they expect input files to contain nothing but the letters, digits, and punctuation on a standard computer keyboard. When editing programs, therefore, you must either use a plain text editor, or be careful to save files as plain text.

Let’s type in a few lines of text.

Once we’re happy with our text, we can press Ctrl-O (press the Ctrl or Control key and, while

holding it down, press the O key) to write our data to disk

(we’ll be asked what file we want to save this to:

press Return to accept the suggested default of draft.txt).

Once our file is saved, we can use Ctrl-X to quit the editor and

return to the shell.

Control, Ctrl, or ^ Key

The Control key is also called the “Ctrl” key. There are various ways in which using the Control key may be described. For example, you may see an instruction to press the Control key and, while holding it down, press the X key, described as any of:

Control-XControl+XCtrl-XCtrl+X^XC-xIn nano, along the bottom of the screen you’ll see

^G Get Help ^O WriteOut. This means that you can useControl-Gto get help andControl-Oto save your file.

nano doesn’t leave any output on the screen after it exits,

but ls now shows that we have created a file called draft.txt:

$ ls

draft.txt

Now let’s tidy up the thesis directory by removing the draft we created:

$ rm draft.txt

This command removes files (rm is short for “remove”).

If we run ls again,

its output is empty once more,

which tells us that our file is gone:

$ ls

Deleting Is Forever

The Unix shell doesn’t have a trash bin that we can recover deleted files from (though most graphical interfaces to Unix do). In other words, if you remove (

rm) something, it’s gone forever! When we delete files in bash, they are unhooked from the file system so that their storage space on disk can be recycled. Tools for finding and recovering deleted files do exist, but there’s no guarantee they’ll work in any particular situation, since the computer may recycle the file’s disk space right away.

Let’s re-create that file

and then move up one directory to /Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell using cd ..:

$ pwd

/Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell/thesis

$ nano draft.txt

$ ls

draft.txt

$ cd ..

If we try to remove the entire thesis directory using rm thesis,

we get an error message:

$ rm thesis

rm: cannot remove `thesis': Is a directory

This happens because rm by default only works on files, not directories.

To really get rid of thesis we must also delete the file draft.txt.

We can do this with the recursive option for rm:

$ rm -r thesis

With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

Removing the files in a directory recursively can be a very dangerous operation. If we’re concerned about what we might be deleting we can add the “interactive” flag

-itormwhich will ask us for confirmation before each step$ rm -r -i thesis rm: descend into directory ‘thesis’? y rm: remove regular file ‘thesis/draft.txt’? y rm: remove directory ‘thesis’? yThis removes everything in the directory, then the directory itself, asking at each step for you to confirm the deletion.

Let’s create that directory and file one more time.

(Note that this time we’re running nano with the path thesis/draft.txt,

rather than going into the thesis directory and running nano on draft.txt there.)

$ pwd

/Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell

$ mkdir thesis

$ nano thesis/draft.txt

$ ls thesis

draft.txt

draft.txt isn’t a particularly informative name,

so let’s change the file’s name using mv,

which is short for “move”:

$ mv thesis/draft.txt thesis/quotes.txt

The first argument tells mv what we’re “moving”,

while the second is where it’s to go.

In this case,

we’re moving thesis/draft.txt to thesis/quotes.txt,

which has the same effect as renaming the file.

Sure enough,

ls shows us that thesis now contains one file called quotes.txt:

$ ls thesis

quotes.txt

One has to be careful when specifying the target file name, since mv will

silently overwrite any existing file with the same name, which could

lead to data loss. Just as for rm, you can use an additional flag, mv -i (or mv --interactive),

to make mv ask you for confirmation before overwriting.

Just for the sake of consistency,

mv also works on directories

Let’s move quotes.txt into the current working directory.

We use mv once again,

but this time we’ll just use the name of a directory as the second argument

to tell mv that we want to keep the filename,

but put the file somewhere new.

(This is why the command is called “move”.)

In this case,

the directory name we use is the special directory name . that we mentioned earlier.

$ mv thesis/quotes.txt .

The effect is to move the file from the directory it was in to the current working directory.

ls now shows us that thesis is empty:

$ ls thesis

Further,

ls with a filename or directory name as an argument only lists that file or directory.

We can use this to see that quotes.txt is still in our current directory:

$ ls quotes.txt

quotes.txt

Moving to the Current Folder

After running the following commands, Jamie realizes that she put the files

sucrose.datandmaltose.datinto the wrong folder:$ ls -F analyzed/ raw/ $ ls -F analyzed fructose.dat glucose.dat maltose.dat sucrose.dat $ cd raw/Fill in the blanks to move these files to the current folder (i.e., the one she is currently in):

$ mv ___/sucrose.dat ___/maltose.dat ___Solution

$ mv ../analyzed/sucrose.dat ../analyzed/maltose.dat .Recall that

..refers to the parent directory (i.e. one above the current directory) and that.refers to the current directory.

The cp command works very much like mv,

except it copies a file instead of moving it.

We can check that it did the right thing using ls

with two paths as arguments — like most Unix commands,

ls can be given multiple paths at once:

$ cp quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

$ ls quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

To prove that we made a copy,

let’s delete the quotes.txt file in the current directory

and then run that same ls again.

$ rm quotes.txt

$ ls quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

ls: cannot access quotes.txt: No such file or directory

thesis/quotations.txt

This time it tells us that it can’t find quotes.txt in the current directory,

but it does find the copy in thesis that we didn’t delete.

What’s In A Name?

You may have noticed that all of Nelle’s files’ names are “something dot something”, and in this part of the lesson, we always used the extension

.txt. This is just a convention: we can call a filemythesisor almost anything else we want. However, most people use two-part names most of the time to help them (and their programs) tell different kinds of files apart. The second part of such a name is called the filename extension, and indicates what type of data the file holds:.txtsignals a plain text file,.cfgis a configuration file full of parameters for some program or other,.pngis a PNG image, and so on.This is just a convention, albeit an important one. Files contain bytes: it’s up to us and our programs to interpret those bytes according to the rules for plain text files, PDF documents, configuration files, images, and so on.

Naming a PNG image of a whale as

whale.mp3doesn’t somehow magically turn it into a recording of whalesong, though it might cause the operating system to try to open it with a music player when someone double-clicks it.

Renaming Files

Suppose that you created a

.txtfile in your current directory to contain a list of the statistical tests you will need to do to analyze your data, and named it:statstics.txtAfter creating and saving this file you realize you misspelled the filename! You want to correct the mistake, which of the following commands could you use to do so?

cp statstics.txt statistics.txtmv statstics.txt statistics.txtmv statstics.txt .cp statstics.txt .Solution

- No. While this would create a file with the correct name, the incorrectly named file still exists in the directory and would need to be deleted.

- Yes, this would work to rename the file.

- No, the period(.) indicates where to move the file, but does not provide a new file name; identical file names cannot be created.

- No, the period(.) indicates where to copy the file, but does not provide a new file name; identical file names cannot be created.

Moving and Copying

What is the output of the closing

lscommand in the sequence shown below?$ pwd/Users/jamie/data$ lsproteins.dat$ mkdir recombine $ mv proteins.dat recombine/ $ cp recombine/proteins.dat ../proteins-saved.dat $ ls

proteins-saved.dat recombinerecombineproteins.dat recombineproteins-saved.datSolution

We start in the

/Users/jamie/datadirectory, and create a new folder calledrecombine. The second line moves (mv) the fileproteins.datto the new folder (recombine). The third line makes a copy of the file we just moved. The tricky part here is where the file was copied to. Recall that..means “go up a level”, so the copied file is now in/Users/jamie. Notice that..is interpreted with respect to the current working directory, not with respect to the location of the file being copied. So, the only thing that will show using ls (in/Users/jamie/data) is the recombine folder.

- No, see explanation above.

proteins-saved.datis located at/Users/jamie- Yes

- No, see explanation above.

proteins.datis located at/Users/jamie/data/recombine- No, see explanation above.

proteins-saved.datis located at/Users/jamie

Copy with Multiple Filenames

For this exercise, you can test the commands in the

data-shell/datadirectory.In the example below, what does

cpdo when given several filenames and a directory name?$ mkdir backup $ cp amino-acids.txt animals.txt backup/In the example below, what does

cpdo when given three or more file names?$ ls -Famino-acids.txt animals.txt backup/ elements/ morse.txt pdb/ planets.txt salmon.txt sunspot.txt$ cp amino-acids.txt animals.txt morse.txtSolution

If given more than one file name followed by a directory name (i.e. the destination directory must be the last argument),

cpcopies the files to the named directory.If given three file names,

cpthrows an error because it is expecting a directory name as the last argument.cp: target ‘morse.txt’ is not a directory

Nelle’s Pipeline: Organizing Files

Knowing just this much about files and directories,

Nelle is ready to organize the files that the protein assay machine will create.

First,

she creates a directory called north-pacific-gyre

(to remind herself where the data came from).

Inside that,

she creates a directory called 2012-07-03,

which is the date she started processing the samples.

She used to use names like conference-paper and revised-results,

but she found them hard to understand after a couple of years.

(The final straw was when she found herself creating

a directory called revised-revised-results-3.)

Sorting Output

Nelle names her directories “year-month-day”, with leading zeroes for months and days, because the shell displays file and directory names in alphabetical order. If she used month names, December would come before July; if she didn’t use leading zeroes, November (‘11’) would come before July (‘7’). Similarly, putting the year first means that June 2012 will come before June 2013.

Each of her physical samples is labelled according to her lab’s convention

with a unique ten-character ID,

such as “NENE01729A”.

This is what she used in her collection log

to record the location, time, depth, and other characteristics of the sample,

so she decides to use it as part of each data file’s name.

Since the assay machine’s output is plain text,

she will call her files NENE01729A.txt, NENE01812A.txt, and so on.

All 1520 files will go into the same directory.

In the current directory data-shell, you can see what files

Nelle has by using the command:

$ ls north-pacific-gyre/2012-07-03/

Don’t forget that you can use Tab completion to make this easier and quicker!

Key Points

cp old newcopies a file.

mkdir pathcreates a new directory.Most files’ names are

something.extension. The extension isn’t required, and doesn’t guarantee anything, but is normally used to indicate the type of data in the file.

mv old newmoves (renames) a file or directory.

rm pathremoves (deletes) a file.Use of the Control key may be described in many ways, including

Ctrl-X,Control-X, and^X.The shell does not have a trash bin: once something is deleted, it’s really gone.

Depending on the type of work you do, you may need a more powerful text editor than Nano.