Creating Functions

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can I teach MATLAB how to do new things?

Objectives

Compare and contrast MATLAB function files with MATLAB scripts.

Define a function that takes arguments.

Test a function.

Recognize why we should divide programs into small, single-purpose functions.

If we only had one data set to analyze, it would probably be faster to load the file into a spreadsheet and use that to plot some simple statistics. But we have twelve files to check, and may have more in future. In this lesson, we’ll learn how to write a function so that we can repeat several operations with a single command.

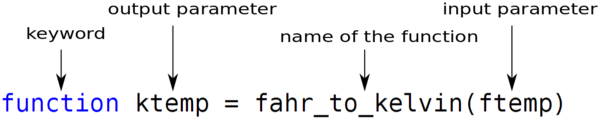

Let’s start by defining a function fahr_to_kelvin that converts temperatures from Fahrenheit to Kelvin:

function ktemp = fahr_to_kelvin(ftemp)

%FAHR_TO_KELVIN Convert Fahrenheit to Kelvin

ktemp = ((ftemp - 32) * (5/9)) + 273.15;

end

A MATLAB function must be saved in a text file with a .m extension.

The name of that file must be the same as the function defined

inside it. The name must start with a letter and cannot contain spaces.

So, you will need to save the above code in a file called

fahr_to_kelvin.m.

Remember to save your m-files in the current directory.

The first line of our function is called the function definition,

and it declares that we’re writing a function named fahr_to_kelvin,

that has a single input parameter,ftemp,

and a single output parameter, ktemp.

Anything following the function definition line is called the body of the

function. The keyword end marks the end of the function body, and the

function won’t know about any code after end.

A function can have multiple input and output parameters if required, but isn’t required to have any of either. The general form of a function is shown in the pseudo-code below:

function [out1, out2] = function_name(in1, in2)

%FUNCTION_NAME Function description

% This section below is called the body of the function

out1 = something calculated;

out2 = something else;

end

Just as we saw with scripts, functions must be visible to MATLAB, i.e., a file containing a function has to be placed in a directory that MATLAB knows about. The most convenient of those directories is the current working directory.

GNU Octave

In common with MATLAB, Octave searches the current working directory and the path for functions called from the command line.

We can call our function from the command line like any other MATLAB function:

>> fahr_to_kelvin(32)

ans = 273.15

When we pass a value, like 32, to the function, the value is assigned

to the variable ftemp so that it can be used inside the function. If we

want to return a value from the function, we must assign that value to a

variable named ktemp—in the first line of our function, we promised

that the output of our function would be named ktemp.

Outside of the function, the variables ftemp and ktemp aren’t visible;

they are only used by the function body to refer to the input and

output values.

This is one of the major differences between scripts and functions: a script can be thought of as automating the command line, with full access to all variables in the base workspace, whereas a function can only read and write variables from the calling workspace if they are passed as arguments — i.e. a function has its own separate workspace.

Now that we’ve seen how to convert Fahrenheit to Kelvin, it’s easy to convert Kelvin to Celsius.

function ctemp = kelvin_to_celsius(ktemp)

%KELVIN_TO_CELSIUS Convert from Kelvin to Celcius

ctemp = ktemp - 273.15;

end

Again, we can call this function like any other:

>> kelvin_to_celsius(0.0)

ans = -273.15

What about converting Fahrenheit to Celsius? We could write out the formula, but we don’t need to. Instead, we can compose the two functions we have already created:

function ctemp = fahr_to_celsius(ftemp)

%FAHR_TO_CELSIUS Convert Fahrenheit to Celcius

ktemp = fahr_to_kelvin(ftemp);

ctemp = kelvin_to_celsius(ktemp);

end

Calling this function,

>> fahr_to_celsius(32.0)

we get, as expected:

ans = 0

This is our first taste of how larger programs are built: we define basic operations, then combine them in ever-larger chunks to get the effect we want. Real-life functions will usually be larger than the ones shown here—typically half a dozen to a few dozen lines—but they shouldn’t ever be much longer than that, or the next person who reads it won’t be able to understand what’s going on.

Concatenating in a Function

In MATLAB, we concatenate strings by putting them into an array or using the

strcatfunction:>> disp(['abra', 'cad', 'abra'])abracadabra>> disp(strcat('a', 'b'))abWrite a function called

fencethat has two parameters,originalandwrapperand addswrapperbefore and afteroriginal:>> disp(fence('name', '*'))*name*Solution

function wrapped = fence(original, wrapper) %FENCE Return original string, with wrapper prepended and appended wrapped = strcat(wrapper, original, wrapper); end

Getting the Outside

If the variable

srefers to a string, thens(1)is the string’s first character ands(end)is its last. Write a function calledouterthat returns a string made up of just the first and last characters of its input:>> disp(outer('helium'))hmSolution

function ends = outer(s) %OUTER Return first and last characters from a string ends = strcat(s(1), s(end)); end

Variables Inside and Outside Functions

Consider our function

fahr_to_kelvinfrom earlier in the episode:function ktemp = fahr_to_kelvin(ftemp) %FAHR_TO_KELVIN Convert Fahrenheit to Kelvin ktemp = ((ftemp-32)*(5.0/9.0)) + 273.15; endWhat does the following code display when run — and why?

ftemp = 0 ktemp = 0 disp(fahr_to_kelvin(8)) disp(fahr_to_kelvin(41)) disp(fahr_to_kelvin(32)) disp(ktemp)Solution

259.8167 278.1500 273.1500 0

ktempis 0 because the functionfahr_to_kelvinhas no knowledge of the variablektempwhich exists outside of the function.

Once we start putting things in functions so that we can re-use them, we need to start testing that those functions are working correctly. To see how to do this, let’s write a function to center a dataset around a particular value:

function out = center(data, desired)

out = (data - mean(data(:))) + desired;

end

We could test this on our actual data, but since we don’t know what the values ought to be, it will be hard to tell if the result was correct, Instead, let’s create a matrix of 0’s, and then center that around 3:

>> z = zeros(2,2);

>> center(z, 3)

ans =

3 3

3 3

That looks right, so let’s try out center function on our real data:

>> data = csvread('data/inflammation-01.csv');

>> centered = center(data(:), 0)

It’s hard to tell from the default output whether the result is correct–this is often the case when working with fairly large arrays–but, there are a few simple tests that will reassure us.

Let’s calculate some simple statistics:

>> disp([min(data(:)), mean(data(:)), max(data(:))])

0.00000 6.14875 20.00000

And let’s do the same after applying our center function

to the data:

>> disp([min(centered(:)), mean(centered(:)), max(centered(:))])

-6.1487 -0.0000 13.8513

That seems almost right: the original mean was about 6.1, so the lower bound from zero is now about -6.1. The mean of the centered data isn’t quite zero–we’ll explore why not in the challenges–but it’s pretty close. We can even go further and check that the standard deviation hasn’t changed:

>> std(data(:)) - std(centered(:))

5.3291e-15

The difference is very small. It’s still possible that our function is wrong, but it seems unlikely enough that we should probably get back to doing our analysis. We have one more task first, though: we should write some documentation for our function to remind ourselves later what it’s for and how to use it.

function out = center(data, desired)

%CENTER Center data around a desired value.

%

% center(DATA, DESIRED)

%

% Returns a new array containing the values in

% DATA centered around the value.

out = (data - mean(data(:))) + desired;

end

Comment lines immediately below the function definition line

are called “help text”. Typing help function_name brings

up the help text for that function:

>> help center

Center Center data around a desired value.

center(DATA, DESIRED)

Returns a new array containing the values in

DATA centered around the value.

Testing a Function

Write a function called

normalisethat takes an array as input and returns an array of the same shape with its values scaled to lie in the range 0.0 to 1.0. (If L and H are the lowest and highest values in the input array, respectively, then the function should map a value v to (v - L)/(H - L).) Be sure to give the function a comment block explaining its use.Run

help linspaceto see how to uselinspaceto generate regularly-spaced values. Use arrays like this to test yournormalisefunction.Solution

function out = normalise(in) %NORMALISE Return original array, normalised so that the % new values lie in the range 0 to 1. H = max(max(in)); L = min(min(in)); out = (in-L)/(H-L); enda = linspace(1, 10); % Create evenly-spaced vector norm_a = normalise(a); % Normalise vector plot(a, norm_a) % Visually check normalisation

Convert a script into a function

Convert the script from the previous episode into a function called

analyze_dataset. The function should operate on a single data file, and should have two parameters:file_nameandplot_switch. When called, the function should create the three graphs produced in the previous lesson. Whether they are displayed or saved to theresultsdirectory should be controlled by the value ofplot_switchi.e.analyze_dataset('data/inflammation-01.csv', 0)should display the corresponding graphs for the first data set;analyze_dataset('data/inflammation-02.csv', 1)should save the figures for the second dataset to theresultsdirectory.Be sure to give your function help text.

Solution

function analyze_dataset(file_name, plot_switch) %ANALYZE_DATASET Perform analysis for named data file. % Create figures to show average, max and min inflammation. % Display plots in GUI using plot_switch = 0, % or save to disk using plot_switch = 1. % % Example: % analyze_dataset('data/inflammation-01.csv', 0) % Generate string for image name: img_name = replace(file_name, '.csv', '.png'); img_name = replace(img_name, 'data', 'results'); patient_data = csvread(file_name); if plot_switch == 1 figure('visible', 'off') else figure('visible', 'on') end subplot(2, 2, 1) plot(mean(patient_data, 1)) ylabel('average') subplot(2, 2, 2) plot(max(patient_data, [], 1)) ylabel('max') subplot(2, 2, 3) plot(min(patient_data, [], 1)) ylabel('min') if plot_switch == 1 print(img_name, '-dpng') close() end end

Automate the analysis for all files

Write a script called

process_allwhich loops over all of the data files, and calls the functionanalyze_datasetfor each file in turn. Your script should save the image files to the ‘results’ directory rather than displaying the figures in the MATLAB GUI.Solution

%PROCESS_ALL Analyse all inflammation datasets % Create figures to show average, max and min inflammation. % Save figures to 'results' directory. files = dir('data/inflammation-*.csv'); for i = 1:length(files) file_name = files(i).name; file_name = fullfile('data', file_name); % Process each data set, saving figures to disk. analyze_dataset(file_name, 1); end

We have now solved our original problem: we can analyze any number of data files with a single command. More importantly, we have met two of the most important ideas in programming:

-

Use arrays to store related values, and loops to repeat operations on them.

-

Use functions to make code easier to re-use and easier to understand.

Key Points

Break programs up into short, single-purpose functions with meaningful names.

Define functions using the

functionkeyword.